One of my earliest memories is my mother bringing me to feed ducks at the park. We fed them bread and didn't know any better - I've since learned what a big problem it is. When I was 6 or 7, I spent hours devising homemade traps to capture sparrows in my backyard using a laundry basket, a stick and string. I never caught any, thankfully, but it gave me great joy to watch flocks of them visit my yard. My mother finally caved in to give me parakeets when I was 10 years old - whom I named fluffy and bluebird.

Fast forward twelve years later, and I am still amazed and captivated by birds, and fortunately no longer trying to capture them in laundry baskets. This summer at Nature Camp I was enamored with a barn owl and a gyrfalcon. I also recently wrote about a great blue heron and its run-in with a bald eagle.

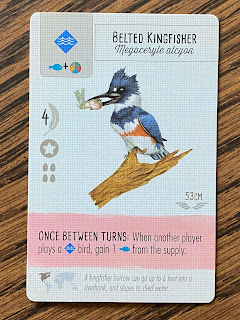

I've gone out a few times with the Northern Virginia Birding Club, the Monday morning Huntley Meadow birding group, and Birdability. I've started to learn more bird songs through playing the eBird quiz and enjoyed many comics drawn by Bird and Moon. I've even played two different bird themed board games - Wingspan and Fly-A-Way. As I have become more involved in various organizations and efforts on wildlife conservation over the past few years, I have noticed myself repeatedly drawn to birds.

In Costa Rica last year, I spent some time with a good friend and expert birder, and had the good fortune to spend a few lazy months watching native birds in between trips to the beach. Then back home in Massachusetts, I spent hours watching birds in the yard - the usual characters - robins, cardinals, bluejays. Then one day I saw a bird I had never seen before. A fairly large bird pulling up worms with the robins after a rain. I looked it up and identified it as a northern flicker.

Photo credit: Pixabay User, Naturelady (

link)

I had literally never in my life heard of this bird. It was amazing to me that there are still birds out there, living beside me, whom I have never seen. It seems incredible. I believe this is one of the reasons that people are captivated by birds. They are everywhere, in every environment - a constant companion - but yet there are enough species to always offer up the awe of seeing a new animal for the first time.

Some other reasons birds captivate us:

- Birds can fly! We all wish we could fly after watching birds outside our windows soaring, gliding, and zooming through the sky.

- Birds are intelligent. We have all seen videos of birds solving complex puzzles - it's impressive.

- Some birds speak. Finally, an animal we can communicate with! While there is debate on how much birds understand what they say, the fact they can imitate our speech (and other sounds) makes them immensely captivating.

- Birds are so diverse. From penguins to emus to owls to kakapos to warblers - birds have evolved into an amazing array of forms to fill ecological niches.

- Birds mating practices remind us of ourselves. David Attenborough's films about birds of paradise and their incredible mating dances remind us of the efforts we go through as humans to attract and impress a partner. Also, some iconic birds mate for life.

Birds also appeal to a large segment of the population - hunters enjoy shooting birds, seniors enjoy watching a serene birdfeeder on their porch, families enjoy feeding ducks (peas not bread, please), birders of all ages enjoy adding to their lifelist, everyone enjoys watching an osprey dramatically striking a fish.

Birds are iconic and for many people they represent nature and the outdoors - and so birds make an excellent mascot when working on habitat conservation. As much as I love snakes, I know that snakes will not produce the warm and fuzzy feelings in the general public that is needed to inspire action. Like the mining canary, the wellbeing of bird species in our community is an indicator of how our ecosystems are faring overall.

In a conversation with my ARMN classmate, Katherine Wychulis, I learned about a harmful insecticide practice that Fairfax County and Prince William County is doing that is negatively affecting bird populations. As described on the

Audubon website,

"The County sprays at a time when many species of birds are breeding, raising young and some birds, especially warblers, are migrating through Northern Virginia. Caterpillars are an important food source for many birds. The insecticide is potentially deadly not just to the targeted fall cankerworm, but to all exposed butterfly and moth caterpillars. These butterfly and moth species, like the fall cankerworm, provide food for birds, beetles, bats, frogs, spiders and other wildlife. And the insecticide, a commercial application of Bacillus thuringiensis subsp. kurstaki (Btk), can "drift" to other areas outside the spray areas."

While the insect they are spraying for can have some negative impact on tree foliage, the populations fluctuate greatly, and the program is not administering the chemical in accordance with population data. This is a problem.

Caterpillars are a crucial food source for birds - especially juvenile birds. I learned recently from ARMN that a nest of three chickadees needs 9,000 caterpillars to grow to adulthood!

If you live in Fairfax County or Prince William County, you can contact your representative to share your concern about this program. To learn more, visit the Audubon Society of Northern Virginia's page on Save the Caterpillars.

Sources: